Recently, I have spent my weekend mornings reading Huston Smith's "Why Religion Matters"--not a new book, but an interesting one, from a religious scholar who writes very accessibly.

The book seems to have come out of a concern about the discarding of a "traditional" worldview, and replacing it with a "scientific" worldview. The concern is a real one, but also a puzzle to me.

The public "battle" between religion and science is extremely evident in controversies in our educational system, and with such issues as a woman's right to choose. "Intelligent design" theory is one example of how science clashes with religion. But I don't think this is a battle between God and the atheists, as it were--it is a battle of worldviews, and both are incomplete.

To begin with--the entire conflict is predicated on the idea that there is some being sitting up in the clouds, directing Earthly traffic remotely. I don't know that anyone really believes this except for hardcore literalists and maybe young children.

Scientific approaches are empirical in nature. They rely on sensory and mathematical data. Scientific method requires a reasonable hypothesis for which measures/experiments are selected that prove or disprove the hypothesis. That may be a bit of a misnomer as well--one doesn't set out to prove that they are right (that represents a bias), and even if experiments go well, they need to be repeated many times before something is accepted as scientific fact. Frankly, there is hardly anything accepted as scientific fact--it's mostly theory, albeit theory well supported by empirical evidence.

So--if you are trying to use scientific methods to prove that there is some being out there in the sky on a golden throne, you will fail.

Smith points out the fact that emotions and emotional experiences (including religious ones) are often discarded in a scientific worldview as being non-objective, and therefore unreliable. This is similar to complaints about psychology, if one takes an extreme Freudian view--religion is merely a wish for a return to an innocent state, or whatever. "Mere" is the key term here--it tries to cut down the power of the experience by dismissing it as something insignificant. Erik Erikson is a bit kinder, distinguishing between those things that are demonstrably true, and those that are felt to be true through internal experience.

Let us turn to the East for a moment. In Buddhism, there is no god-concept. Hinduism has many deities, but they represent one Reality. There are actually 3 types of Hindu worship—bhakta (devotion), tantra, and vedanta. Vedanta is very similar to Buddhism in this respect—there is no-thing to worship. Ammachi has said that atheists are no more right or wrong about God than religious folk—no one has a true “image” of the Ultimate (as that would limit the Ultimate—and break the first commandment, if you are Christian or Jewish), so having no concept may be closer to the truth.

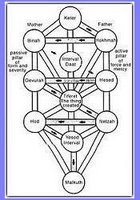

Jewish mysticism has an interesting metaphor for this—the Kabbalistic Tree of Life. The menorah displayed at Hanukah is one version of the Tree of Life, but more often it looks like the picture shown above.

The Tree of Life is made up of 10 “vessels”, or sephiroth. The Tree technically hangs upside down, and is light at the top, and dense at the bottom. Malkuth, the bottom sephiroth, is the Kingdom—it is where we are now. Directly above Malkuth is Yesod, which is represented by the Moon. The Moon reflects the light of the Sun, and is representative (among other things) of one’s Intuition.

Above Yesod are 2 sephiroths—Hod on the left, and Netzach on the right. All of the sephiroth have many qualities, but it may be easiest to think of Hod as Intellect, and Netzach as Emotion. Directly above these 2 is Tifareth, which is a very complex sephiroth—it is the point of realization that one is “connected to God” (we are special), but it is also dangerous—one can start to think they are more special than everyone else. One can rise to spiritual heights, or fall down from here.

Here is the relevant metaphor: If our physical life can be represented as Malkuth, then the 3 sephiroth above represent our “tools”—the Intellect/Rationality, our Emotions, and our Intuition. Useful tools, but each limited in their own way.

In the bigger picture—the Tree of Life is one, and represents the Ultimate in its entirety. And that’s the key—EVERYTHING is part of the Ultimate, and one sephiroth is not more important than another sephiroth. Rationality does not overshadow the others.

Back to the East—to “know God” is to be aware that one is a small part of a larger system, of Primal Consciousness (adiparashakti). To re-use a metaphor—it’s recognizing the strength of flowing with the entire Ocean, rather than struggling to maintain an identity as a wave. One is much more powerful with the whole than as a part.

The problem is that Western religion frequently separates God from the world, and we start looking for something transcendant that can only be realized immanently. There is nothing for “science” to prove. In the divination system of Norse runes, Ralph Blum’s “Book of Runes” notes for the rune Sowelu (wholeness)—“What you are striving to become is what, by nature, you already are. Become conscious of your essence and bring it into form, express it in a creative way."

Namah Shivaya.